How can it be so cold in a warming climate?

Look beyond what you see

Stepping outside in January when the temperature is 10 to 20 degrees below normal makes it difficult to believe that the climate is warming.

And yet, that is the case.

Regarding the recent polar outbreak in the United States, remember what Rafiki suggests in The Lion King, “Look beyond what you see.”

Although climate and weather are intrinsically tied together, they are not the same thing. Weather describes the conditions at a specific place for a short period of time. A couple of hot days in the summer, an individual hurricane, and a week-long polar outbreak are all examples of weather.

Climate is the long term average of that information over multiple years — or longer. For example, a quick check of the data shows the average January temperature over the last 30 years in Minneapolis is 16.1 degrees. Watching how that long term average changes over decades tells us whether or not the climate is changing.

The dreaded polar vortex

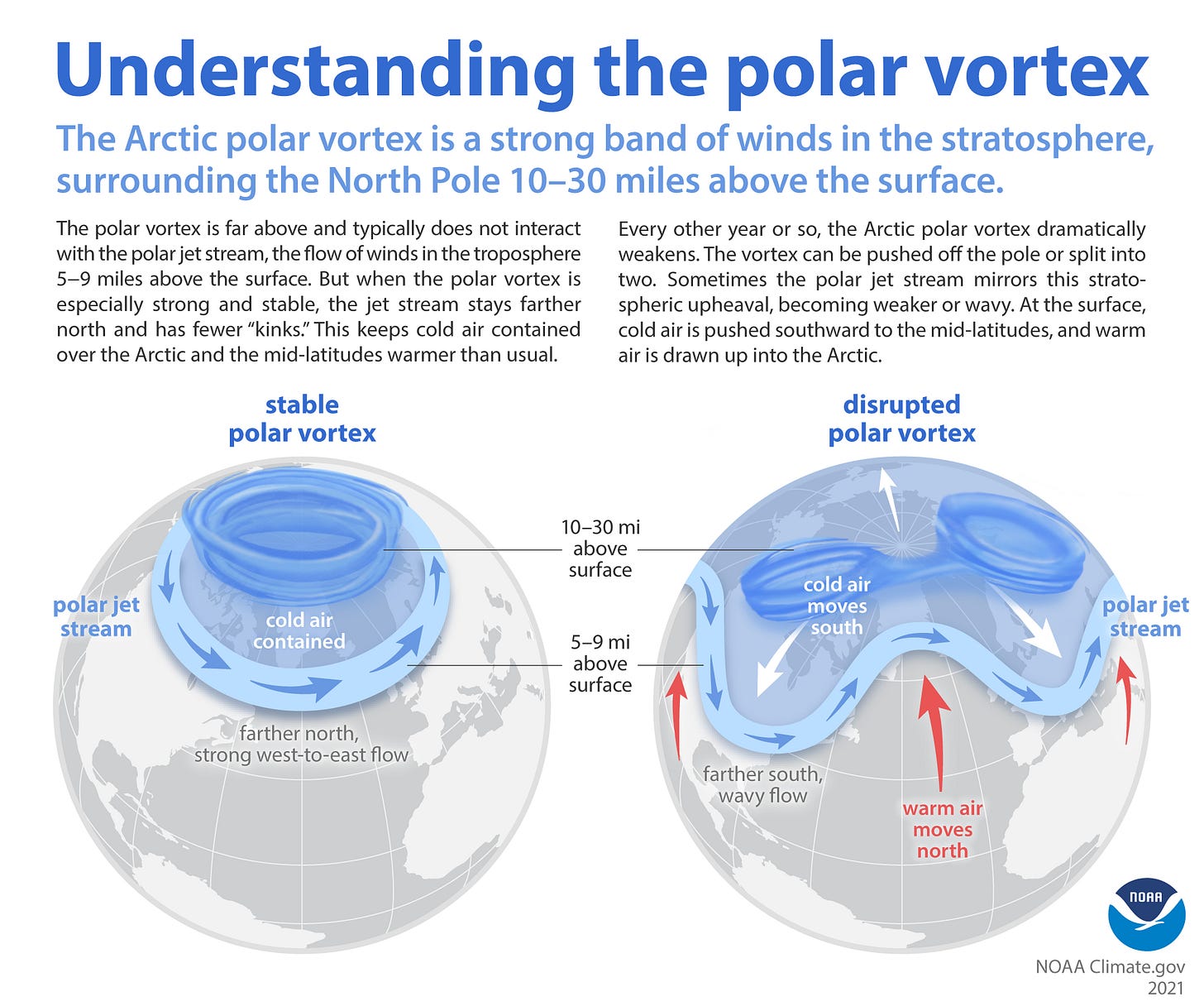

You may have probably heard of the polar vortex, which is a pool of cold air that spirals around the Arctic.

The vortex does not go around the North Pole in a perfect circle, there are waves that travel along that path. Occasionally, one of those waves breaks off, and its winds move south for a while before retreating to the Arctic. Sometimes those waves move south over Europe, sometimes Asia, and sometimes deep into North America. But that quick polar intrusion is the reason for the cold headlines over the last several days.

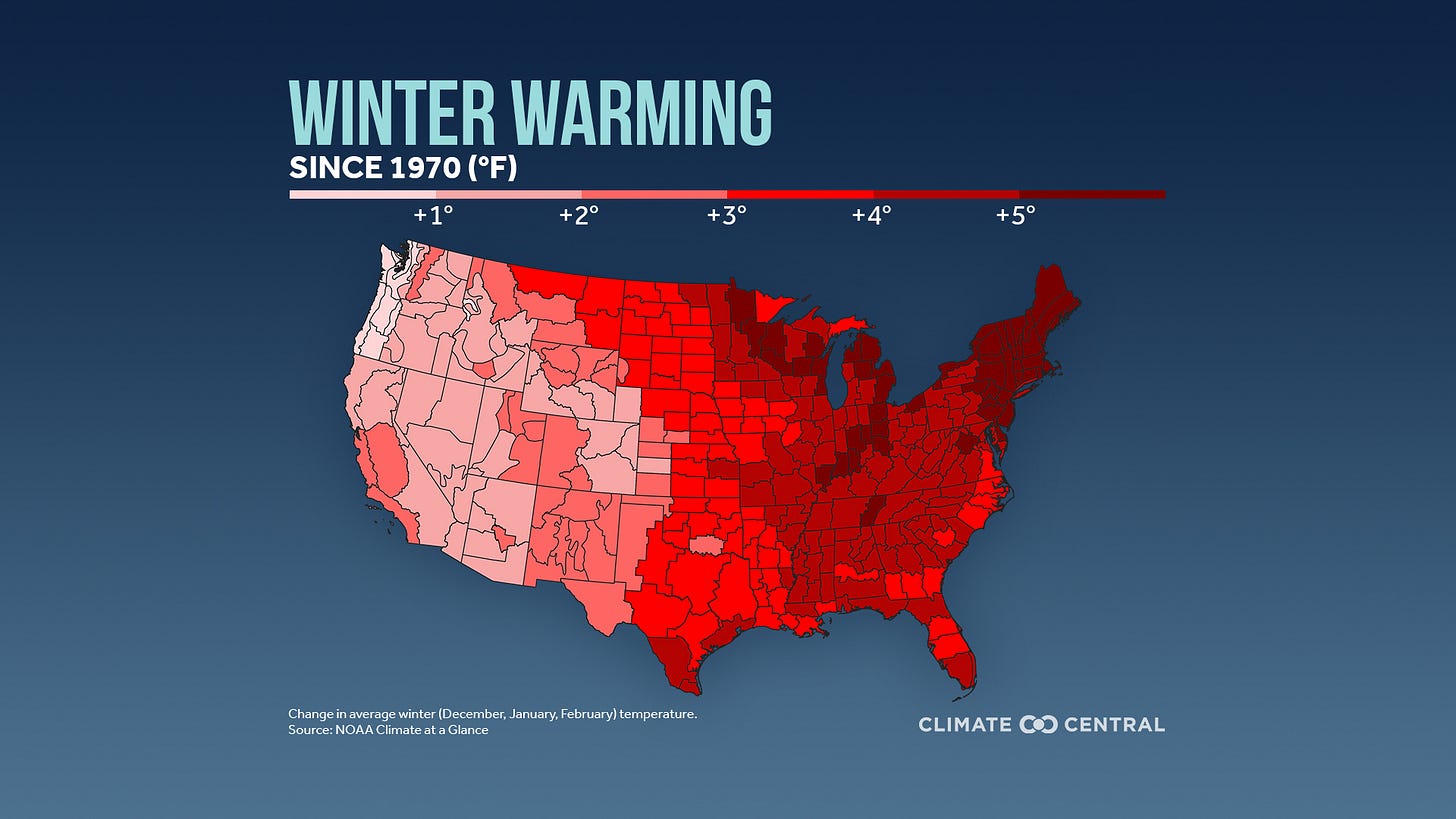

However, these types of bitter cold outbreaks are not occurring as often as they have in the past. In the case of Minneapolis, the average January temperature during the first 30 years of the 20th century was 12.6 degrees, meaning the climate there is now 3.5 degrees warmer than a century ago. Over time, this impacts life in Minnesota — from outdoor winter recreation to an increase in insects that survive the winter (note: graphic above only shows full winter temperatures since 1970 — suggesting warming has accelerated).

Among the most active research topics in the climate science community is how the polar vortex will react in a warming climate. There is evidence that the vortex will become more wavy, more often. In turn, that would suggest surges of polar air move southward more frequently.

But, as the climate warms, the actual air in the Arctic is also warming. So once that air arrives in the United States, it is not as cold as it would have been several decades ago. In the past 50 years, the average winter temperature has increased nationwide. And the largest rises are in some of the coldest climates of the country: the Great Lakes and the Northeast.

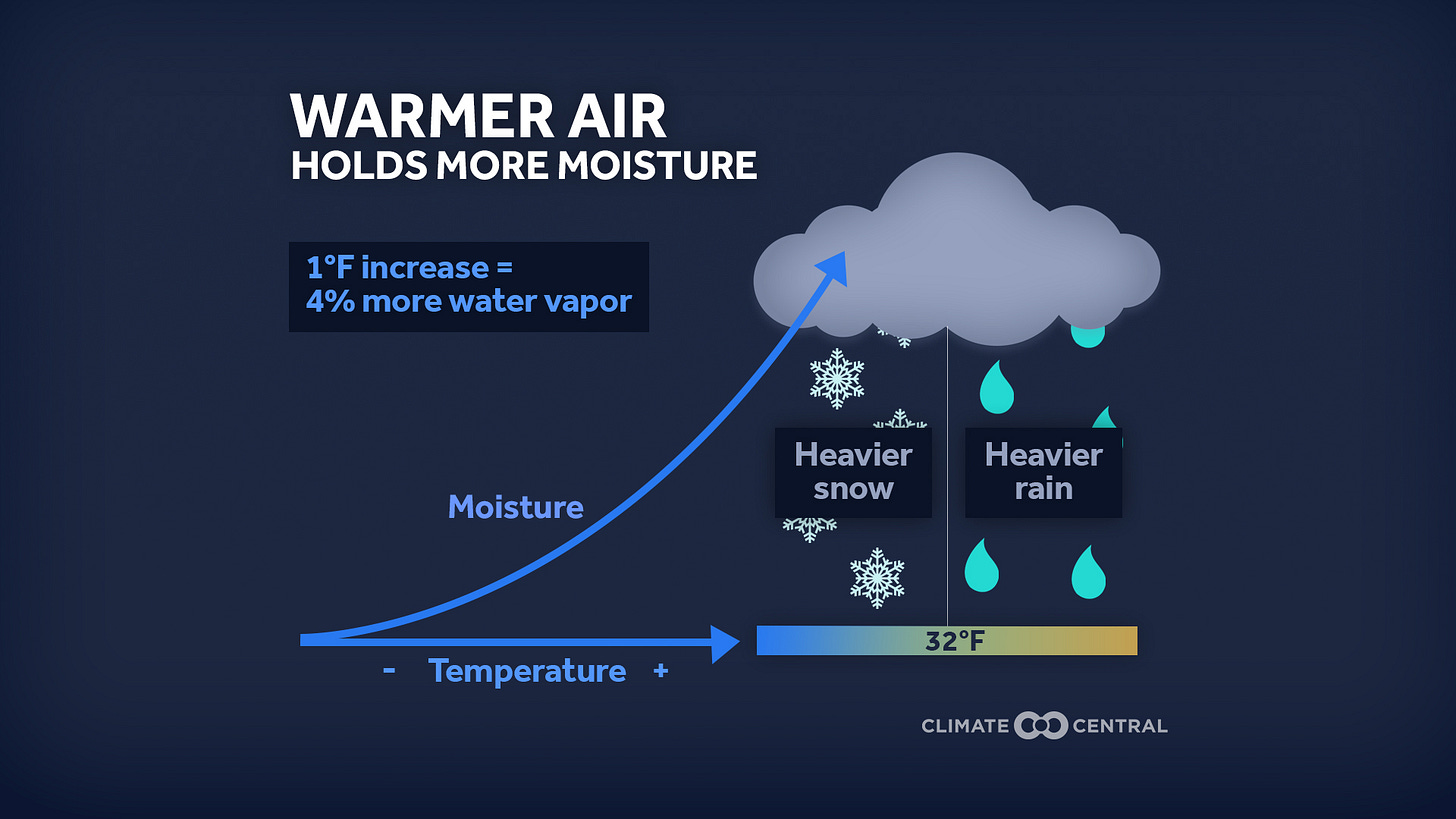

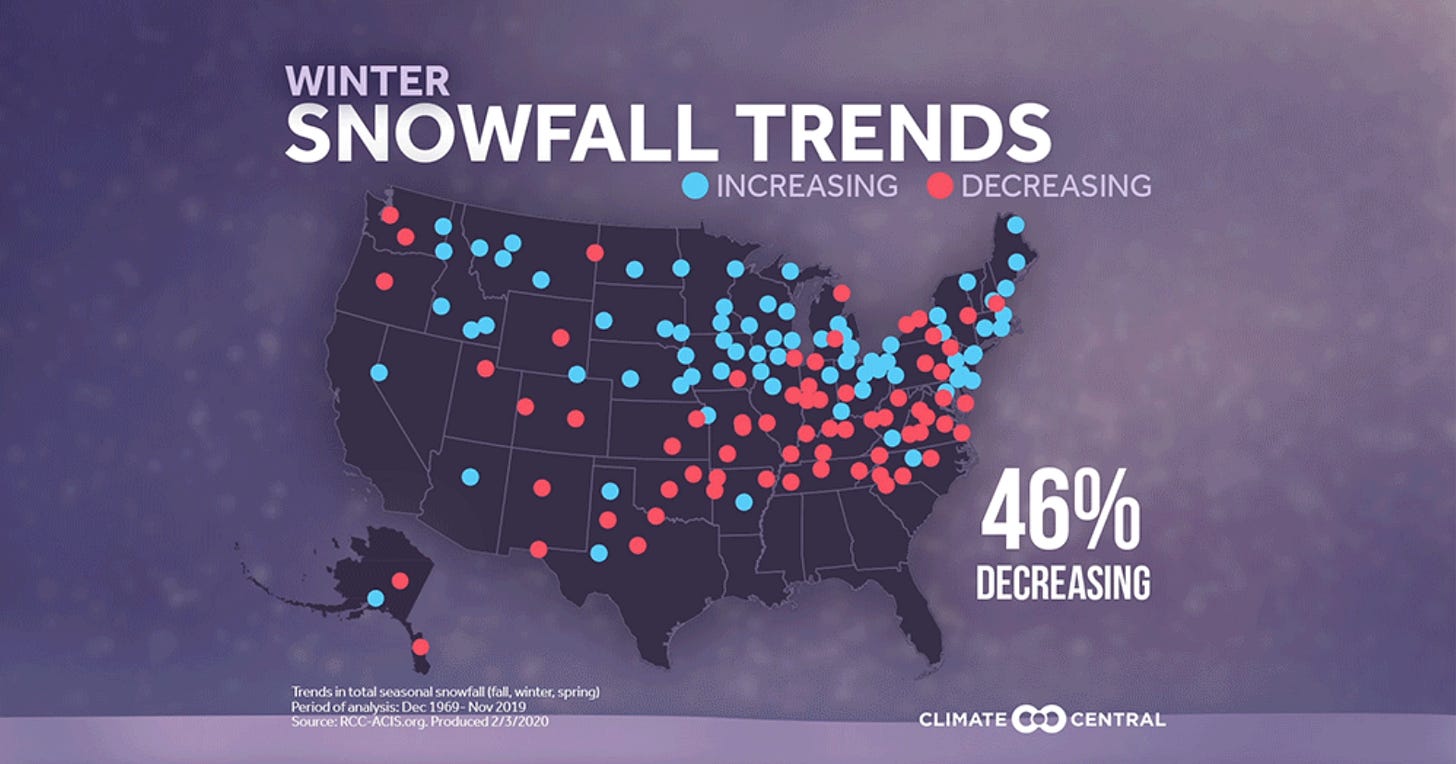

Paradoxically, in those climates that are especially cold to begin with, the amount of snow has increased over the past few decades. A fundamental property of warmer air is that it holds more water vapor than colder air — whether that temperature is above or below freezing. All else being equal, a winter storm at 25 degrees will have more moisture available than one at 20 degrees. In each case, the temperature is below freezing, so there is snow. But there will be more snow in the relatively warmer storm.

Farther south, where winter temperatures more frequently teeter close to the freezing point, snow has been decreasing.

Multiple scientific labs calculated 2023 as the warmest year on record globally, and NOAA reported it as the 5th warmest in the United States, so the warming trends continue. To be sure, winter will still be winter, but the intensity, extent, and longevity of winter cold will continue to decline.